It's the story the New York Times didn't get. Only a local paper with local connections could confirm this kind of information...Believe it.

And congratulations to everyone who called and wrote and delayed the hearing on this insane ban!

Read the Voices Dec07 issue PDF here --- or read the article here:

Learn more and discuss it In our Artificial Growth Hormone Labeling Forum!

Dairy Industry Forces rBST-free Label Ban

VOICES December 2007 Susan Erem

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Monsanto, known for its previous safety claims about PCBs

and Agent Orange, also claims Posilac (rBST) has no impact

on human health.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

One way or another, Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture Secretary Dennis Wolff is going to have to pay.

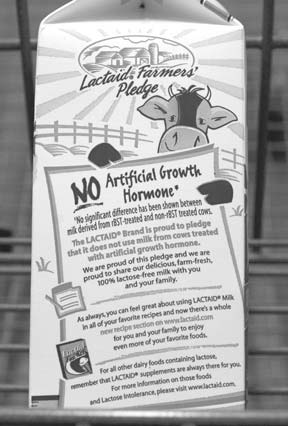

In October, under pressure from the dairy industry, Pennsylvania became the first state to ban the practice of labeling milk as free from Monsanto’s artificial growth hormone rBST. To hedge its bets in case the label ban didn’t go through, the industry has also been demanding compensation (an estimated quarter million dollars per day) for farmers who use rBST if market demands force them to drop use of the drug. The industry has been organizing for more than a year to reduce the growing demand for rBST-free milk.

Pennsylvania now faces the threat of lawsuits from activist groups, rBST-free dairy processors and retailers for everything from the cost of changing labels to lost business to violations of free speech and interstate commerce.

The decision by the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture came less than two months after the Federal Trade Commission denied Monsanto’s demand to investigate what the company called misleading labeling. rBST is also known as rBGH and by its brand name Posilac.

The regulations, revived from decades ago, ban producers from, among other things, making a “production-related claim that is supported solely by sworn statements, affidavits or testimonials.” As a result, statements such as “Our farmers pledge this milk came from cows not injected with artificial growth hormone” would have been illegal as of Jan. 1, 2008. But as Voices went to press, the ban was postponed at least a month due to public pressure.

"All of us who have kids are pretty

clear with them why performance

-enhancing drugs are not used in

sports, so how do we tell our kids

that the milk they drink in the

mornings can be produced with

performance-enhancing drugs?"

--Brian Snyder

“Consumers have expressed a great deal of concern over food labeling practices,” the department question-and-answer materials state. “Many feel that labeling and marketing practices are misleading from a health and safety standpoint, making it hard to make informed decisions.”

“This is censorship,” Rick North, project director of Oregon Physicians for Social Responsibility’s Campaign for Safe Food, told Voices. “This isn’t about protecting consumers. This is about protecting Monsanto’s dwindling profits.” The group is a vocal national critic of the artificial growth hormone.

Andrew Martin agreed in a Nov. 11 New York Times commentary.

“[Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture Secretary] Wolff’s edict doesn’t have anything to do with helping consumers. Otherwise, he would have tried to refine the labels or create a system for verifying dairy farmers’ claims,” wrote Martin in the Times Business section.

But a major local dairy farmer disagreed.

“The problem is all milk is free of antibiotics and a lot of things the labels are trying to differentiate,” explained Abe Harpster, co-owner of Harpster Farms, a 2,000-head-plus dairy in Centre and Huntingdon counties. “In fact, all milk doesn’t have what the labels are saying. It’s taking some milk and making it look bad by portraying other milk as better when it really isn’t.”

The Federal Drug Administration approved Posilac in 1993 while Michael Taylor (former Monsanto attorney who returned to Monsanto in 1998) was deputy commissioner.

The state Department of Agriculture claims that in October 2007, it called together a “group of dietitians, consumer advocates and food industry representatives” that became its Food Label Advisory Committee. This committee agreed that “absence labeling specifically is misleading consumers.”

Of the 15 organizations invited to serve on the committee, only one is a known rBST-free advocate, Pennsylvania Certified Organic. When asked for the list of individuals who attended the October meeting, Department of Agriculture spokesperson Chris Ryder said no attendance was taken.

Milk mathematics

Pennsylvania is the fourth largest dairy state, with an estimated 560,000 cows, according to May 2007 Penn State Agricultural Sciences statistics. An estimated 30 percent, or 168,000 cows, are injected with Posilac, regulators and dairymen said.

“They’re going to lose a gallon of milk per cow [per day],” explained Professional Dairy Managers of Pennsylvania President Logan Bower, who operates a dairy with more than 500 cows in Blair County. “And it’s roughly a buck and a half at today’s milk prices,” he said.

That translates into a net loss of $252,000 per day to Pennsylvania dairy farmers. (Well, at least to some—Posilac tends to be used by larger dairy operations.) This doesn’t include the revenue lost by Monsanto, which enjoys representation in every major dairy promotion group in the state. At 38 cents per cow, a figure provided by Bower, Monsanto is taking in almost $64,000 per day in Pennsylvania on Posilac alone.

So it was worth it for Monsanto Dairy’s Kevin Holloway to make this demand at a September 2006 industry meeting:

“Buyers of specialty milk should pay [for] a farmer’s choice to use safe, effective technology,” Holloway said. “At a minimum, this premium should be guaranteed to pay for lost profitability, handling and verification costs of specialty milk. This guarantee should last as long as a producer is required to give up the choice.”

In other words, processors, retailers and/or consumers should pay farmers for not injecting their cows with artificial growth hormones.

Could Monsanto and its year-long organizing drive exert enough pressure on Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture officials to sway them to make rBST-free claims virtually invisible to the public with this new regulation?

“Knowing there was some consumer demand for hormone-free milk, as consumers see that, knowing dairies were making that demand, and knowing that producers were going to lose production by not using rBST…yes, that created some momentum for this decision,” admitted Cheryl Cook, deputy secretary for marketing and economic development for the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture. Cook said farmers “all over the state” as well as dairy promotion groups approached the secretary with demands for compensation, yet she admitted the department has never calculated what that would cost.

Monsanto has been advocating this pricey alternative for more than a year, and dairy promotion groups have echoed the logic repeatedly.

“If you want affordable, safe domestic agriculture, then there are certain things that come along with that,” explained Alan Novak, lobbyist and executive director of the Dairy Managers group. “That affordability comes into question here.”

“Wait a minute, their compensation is in part that they still have access to some of the markets they want,” said Penn State agricultural economist Tim Kelsey. “It’s not an issue of the government saying, ‘You shall no longer produce milk with rBST.’ It’s a matter of some major customers saying, ‘We no longer want to buy milk made with that hormone.’” Kelsey referred to the popularity of the protein-rich Atkins diet in the 1990s. Many consumers stopped eating bread, but no one compensated bakeries, he said.

But dairymen Bower and Harpster both said it isn’t consumers who are driving the demand for rBST-free foods.

“It was more driven by marketers who had the idea they could charge an extra nickel or quarter and profit by selling this product,” Bower said. “In those efforts they have confused and misled the consumer, and they have profited from it and the producers will end up paying the bill.”

North, whose physicians’ group has campaigned for more than four years on the issue, said consumers are very much behind the drive.

“The consumer demand is overwhelming; this is what consumers want,” he said. “I’ve gone to businesses, Rotary Clubs, universities, moms clubs, and I can tell you this: Once people find out about rGBH, many of them don’t want anything to do with it.”

As for farmers and processors who see losses in their future, North said to listen to the market.

“Switching to rBGH-free is not only the right thing to do for a processor, it’s the smart thing to do, because that’s where the money is,” he said.

The magic of the market

Monsanto’s labeling victory in Pennsylvania is the latest in a long string of battles that the company and its opponents have fought since rBST was approved 14 years ago.

A 1999 study by the University of Wisconsin showed that 74 percent of consumers were concerned about the process of injecting cows with artificial hormones. With recent food scares, awareness of food safety has grown. In a 2007 poll conducted by advocacy group Food and Water Watch of 1,000 adults living in the United States, 80 percent said producers who don’t use rBST should be allowed to label their milk as such.

“This is about the point of purchase being [a] place to educate the consumer,” said local resident Jon Clark, an attorney and Penn State graduate student. “It’s one of the few places where we can get information about the agri-food system behind the food. We need to claim that area, and they’re trying to shut that down. They’re trying to depoliticize the supermarket.”

Until now, the industry has been largely unsuccessful. More and more large dairy processors and retailers are demanding that milk producers go rBST-free.

Starbucks jumped on the bandwagon in 2007, as did Chipotle Mexican Grill, a chain of more than 530 restaurants. Dean Foods, the country’s largest dairy processor, has converted to rBST-free production in a number of New England plants, and Safeway, one of the country’s largest grocery chains, has gone rBST-free in the Northwest. Costco, Kroger, Trader Joe’s and Whole Foods Market sell rBST-free products.

So it’s beginning to look a lot like eroding market share for cows pumped up on Posilac. And that’s a bottom line not lost on Monsanto, which announced just days after Pennsylvania’s ban on rBST-free labels that its gross profits should double in the next five years, according to the Times’ Martin.

Equal and opposite Ph.D.s

Posilac is promoted extensively and unapologetically by Penn State Dairy and Animal Science Department head Terry Etherton, who has gone so far as to calculate that rBST-free milk is selling at prices 36 percent higher than regular milk, according to a recent survey.

“They’re buying a product for the same price but selling one at a higher price,” Etherton said of processors who charge retailers a premium for rBST-free milk.

Harrisburg Dairies, according to its spokesperson and other dairy farmers, pays farmers top dollar for rBST-free milk. But Etherton’s main complaint is that processors don’t pass the premium price they get at one end to the farmers at the other.

“It’s subtle extortion by processors,” Etherton charged of processors demanding rBST-free milk from farmers. He said dairy farmers are dealing with a perishable commodity that can’t be shopped around easily, causing higher hauling costs if they wish to continue to inject their cows with the artificial growth hormone.

But if rBST-free milk draws a higher price simply because of its perceived value among consumers, why wouldn’t all farmers want to go rBST-free and enjoy that premium?

“I don’t think the market share is that big,” Etherton responded. “So I don’t think the producer will get that from the processors.”

Monsanto, known for its previous safety claims about polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and Agent Orange, also claims Posilac has no impact on human health.

So in the land that has proven the tenet “for every Ph.D. there is an equal and opposite Ph.D.,” scientists like Etherton have been working hard to contest the evidence collected by other scientists, most of whom are not located at land grant universities that have much of their research funded by agricultural corporations like Monsanto. Etherton denies the charge made by many rBST-free milk advocates that he or his university are bought and paid for by the likes of Monsanto.

“That’s nonsense,” he said of the charge. “They pay my plane ticket. I don’t get an honorarium or any profit from them.” He admitted that in the early 1980s Monsanto funded his research associated with rBST, but said that his department receives no funds from the company and that as department head he doesn’t currently have a research program.

Most scientists agree that it is almost impossible to detect the artificial hormone in milk, but how it affects the cows is what concerns many consumers, as well as farmers who have decided not to use it. The Posilac label warns, among other things, that the drug may increase incidents of mastitis, a painful condition of the cow’s udder, but some farmers have witnessed worse.

Farmer Charles Knight had to replace most of his herd due to ailments he attributed to the use of Posilac, according to research by Fox TV investigative reporters Steve Wilson and Jane Akre, a husband-and-wife team fired by the broadcast company after they blew the whistle on its Monsanto-friendly rewrite of their report.

“He is one of many farmers who say they’ve watched Posilac burn their cows out sooner, shortening their lives by maybe two years,” the original report states. “Knight says he had to replace 75 percent of his herd due to hoof problems and serious udder infections. Those are two of more than 20 potential troubles listed right on the product warning label.”

Knight’s experience mirrors well-circulated Canadian research that showed increased mastitis, lameness and failure to conceive among cows treated with rBST. The research, coming on the heels of the FDA’s approval of the drug in 1993, has been used to ban the artificial hormone in Europe, Japan, Australia, New Zealand and Canada.

Oregon Physicians for Social Responsibility and Food and Water Watch have both collected extensive documentation of published research that indicates a correlation of rBST use and health problems in animals and research that indicates the potential of rBST to contribute to health problems in humans, but the industry continues to state there is no health risk associated with rBST.

Opponents say Posilac’s label is enough to raise concerns. Farmers treat mastitis with antibiotics, and an increase in mastitis means an increase in antibiotic use. Agriculture Secretary Wolff, himself a dairy farmer, assures the public that milk is tested 10 times for such things as antibiotics before reaching the public, yet a Wall Street Journal investigation found 20 percent of milk tested independently had illegal antibiotics in it, according to a report by Chris Bedford of the Animal Welfare Institute.

“Other studies have found 38 percent higher levels. These antibiotics can contribute to antibiotic resistance in human consumers,” Bedford reported. A further analysis of the original FDA approval study netted even more worrisome details.

“Normal pasteurization heats milk to 168 degrees for 15 seconds to destroy bacteria and other contaminants. The FDA approval study, conducted by a Canadian undergraduate named Paul Groenewegen from Guelph, Canada, cooked the milk for 30 minutes, one hundred and twenty times longer than commercial production practice. According to Groenewegen, only 19 percent of the rBGH and IGF-1 were destroyed in the FDA study’s extended pasteurization process, not the 90 percent claimed by the agency,” Bedford reported. IGF-1 is an insulin-like hormone that affects growth and development.

“It’s not the science, stupid”

Locally, activists and others haven’t been sucked into the science of the issue. Centre Hall resident and farm activist Brian Snyder said it’s also an ethical issue.

“All of us who have kids are pretty clear with them why performance-enhancing drugs are not used in sports, so how do we tell our kids that the milk they drink in the mornings can be produced with performance-enhancing drugs?” Snyder is executive director of Pennsylvania Association for Sustainable Agriculture, which is building a coalition of groups organizing to reverse the labeling rule.

Clark agreed.

“Terry Etherton and other scientific supporters of rBST attempt to frame the controversy as if health risks were the only issues that mattered to the public. This is the ‘riskification’ of controversies that are about much more than just risk,” he said. “Some people might not want to drink milk from cows injected with rBST for reasons that have nothing to do with risk. Maybe I don’t like Monsanto, or maybe I don’t like it when cows are treated as if they were milk factories.”

Even processors see reasons other than health risks for going rBST-free.

“Some people feel they need this management tool in order to run their business, and I would not begrudge them that,” said Betsy Albright of Harrisburg Dairies, which only contracts with farmers who pledge not to use rBST. The dairy recently changed its labels to reflect the practice. “What we are doing is responding to our market.”

So while Monsanto and big industry have been able to raise the issue of lost revenue with Harrisburg officials, and raise the expectation among farmers that they should be compensated for market forces working against them, current rBST-free dairies and producers now face lost revenue themselves if they can’t differentiate the source of their products from rBST-injected cows. And they can add to that the cost of changing labels and other transport and production processes they put in place in good faith under FDA guidelines.

Deputy Secretary Cook said addressing that concern is a likely outcome of this debate.

“We’re going to have to give them some opportunity to prove it, and that only can happen through an independent check, something short of a full-blown organics check,” she explained. “Let’s have the conversation in six months or a year.”

Then there’s the interstate commerce issue.

“Pennsylvania is closing all of its borders to any product that is rBST-free,” explained Albright. “Absolutely nothing can be sold in this state that is labeled rBST-free. A lot of people ship product into this state, and they’re going to choose not to do so.” Harrisburg Dairies, Albright said, imports its cottage cheese from Wisconsin. “They are probably not going to ship us product here because they can’t logistically label their stuff for Pennsylvania differently than [for] any other state.”

“A supermarket could challenge this,” said Clark, reviewing the new regulations. “I would argue that this is an unconstitutional interference with interstate commerce.”

What comes next?

PASA’s Snyder said the story won’t be over soon. One of the group’s first jobs is to rebut the Department of Agriculture’s claims about the source of the problem.

“We have to expose the fact that this move has not been instituted on behalf of consumers like the department is saying,” he said. “Consumers are not demanding to get less information. That’s just common sense.”

And like many advocates for rBST-free products, Snyder was quick to state that the farmers are not to blame here, and they deserve to make a living wage for the work they do.

“I would not blame any farmer for using it, because it’s being marketed to them as something that’ll give them a competitive edge,” he said of rBST. “But as soon as they buy it, Monsanto’s going to go to their neighbor and sell it too, so now who’s got the competitive edge? Only one company. It’s a substance we do not need.”

Pennsylvania officials are not concerned.

“We have the regulatory power to do this,” said the Agriculture Department’s Cook. “We’re on fairly solid ground as far as legal authority. If by raising all this we can prompt the FDA to act, then good for everybody—we’ll get some uniformity in the industry.”

Finally, because no test exists that effectively detects rBST in milk, if the label decision is reversed, consumers will still only have the sworn word of a farmer who promises he doesn’t use it, a nearly unenforceable claim, regulators say.

For more information

Pennsylvania Association for Sustainable Agriculture

Terry Etherton’s blog

http://blogs.das.psu.edu/tetherton

Food and Water Watch

http://www.foodandwaterwatch.org

Original Fox News report

Oregon Physicians for Social Responsibility

Campaign for Safe Food