![]()

by Bryan Farrell

When it comes to replicating war, films like Saving Private Ryan or even the video game Call of Duty have nothing on a football game at Beaver Stadium. Underscoring George Carlin’s famous rant describing the sport as a “20th century new-world-order paramilitary power struggle,” fans at last spring’s Blue-White Game were treated to more than just the typical combat metaphors of “blitz” and “aerial assault.” At halftime, attendees were asked to applaud the choice to join the military during a mock swearing-in ceremony held at midfield for high school students who had recently enlisted.

This encroaching militarization of American culture conjured scant resistance. The lone voice of dissent to appear in the area newspapers came from a class of ’83 alumnus who attended the game. His fellow letter-to-the-editor writers—most of whom were students—roundly dismissed his questioning of “whether participating in the military is still the right thing to do” when “our leaders ignore international law, national and world opinion.”

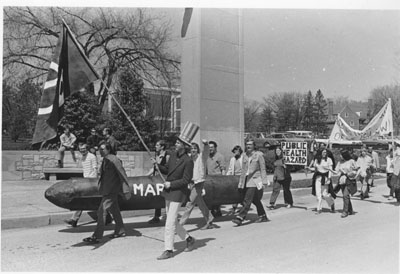

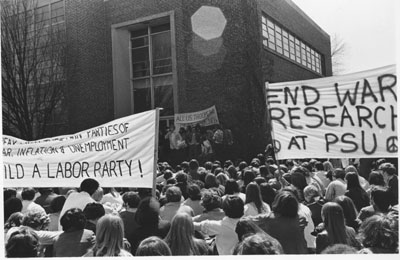

There was a time, however, when college campuses were the epicenter of anti-war sentiment. In 1972—around the same time Carlin debuted his football bit, not coincidentally—thousands of Penn State students protested the Vietnam War by sealing off the entire State College business district for a day and then surrounding the Applied Research Laboratory on campus—a major Department of Defense contractor—forcing it to shut down for three days.

The campus climate in 2008, on the other hand, is much less volatile. The major reason is, no doubt, the absence of a draft, but with more than five years of war in Iraq and Afghanistan, the prospect of another war in Iran and a slew of domestic issues directly affecting the nation’s youth—namely debt, inflation, access to health care and a faltering climate—it’s surprising that the weekly peace vigils at the Allen Street gates remain modest in number.

“Very few students have participated in the Iraq-era actions,” said State College Borough Council member and Peace Center Treasurer Peter Morris. “Some show up at the big ones, like the fifth anniversary.”

But when “big” only amounts to 150 participants—of which a dozen or so are students, by Morris’ estimate—the difference on campus between now and previous war times is “night and day.”

Perhaps this silence is a result of how little Penn State students know about the deep-seated and influential military culture that has taken hold of the university, particularly at their expense.

Since 2000, universities have seen defense-related research contracts increase 900 percent, from $4.4 billion in 2000 to $46.7 billion in 2006. As recently as 2003, Penn State ranked 48th on the Department of Defense’s Research Development Technology and Expenditure Top 100 list, pulling in nearly $63 million in contract awards. But when all forms of Defense Department funding get added in—for a number of obscure or untraceable projects—the grand total is slightly more than $75 million.

Given that more than 50 percent of income tax dollars goes to the Pentagon, students and their parents are, in effect, helping to pay this bill. And with tuition rising another 5.9 percent this coming school year—the 41st consecutive tuition increase at Penn State—it’s no wonder two-thirds of the student body are in debt.

Meanwhile, the university pulled in $1.6 billion in endowment funds last year, a 20 percent increase over the previous year, making it the 46th wealthiest university in the country. Not surprisingly, such corporate gifts come from defense contractors like Lockheed Martin and Exxon Mobil, which, in exchange, get the privilege of recruiting students to work for the war machine.

Since Penn State is home to one of the U.S. Navy’s top civilian research facilities, the aforementioned Applied Research Laboratories, science and engineering students are a prized commodity to the ever-expanding defense industry. ARL, which was founded in 1945, has also become the university’s single largest research unit, with well over 1,000 employees and students working under its umbrella.

Penn State taps the “nonlethal” weapons market

Aside from the labs’ longstanding work on traditional combat technologies—such as hydrodynamics, propulsors and torpedo defense—ARL has branched out into a field that’s being touted by many military experts as the future of warfare, known best as nonlethal weapons.

Initially funded by a $42.5 million five-year contract with the U.S. Marine Corps in 1998, ARL’s Institute for Non-Lethal Defense Technologies continues to pull in millions more every year for what INLDT Director Andy Mazzara calls “a tremendously altruistic endeavor.”

While the fundamental purpose of these weapons is to resolve a conflict without anyone getting killed—a far superior objective to typical combat or law enforcement—the benevolence Mazzara describes comes with several caveats.

First is the issue of effectiveness. Although there are no actual rules governing nonlethal weapons, most experts agree that for a weapon to be a weapon, it must produce the same results on everyone. And for a weapon to be truly nonlethal, it must not cause serious harm or injury.

That simply has not been the case with Tasers, perhaps the most well-known nonlethal weapon. According to Amnesty International, there have been more than 290 Taser-related deaths since 2001. Some have even been ruled homicides, as with the 21-year-old Louisiana man who was shot nine times with a Taser while in handcuffs last January.

“Whenever a nonlethal weapon or technology causes a serious injury or death, there is always concern,” said Mazzara, whose researchers at the INLDT routinely test Tasers. “But the incidence of serious injury and/or death seems to be extremely remote when compared against the actual numbers of employment.”

That might be somewhat reassuring if the overall use of Tasers weren’t on the rise. In 2002, there were roughly 2,000 law enforcement agencies using Tasers. By 2007, that number had risen to 11,500, encompassing two-thirds of all U.S. police departments. The U.S. military has also recently deployed Taser-mounted robots in Iraq.

Another device being tested by the INLDT is the Light Emitting Diode Incapacitator, which was developed by a company in California. It produces a bright and pulsating light that temporarily blinds and disorients its subject so authorities can safely subdue the person. But according to the developers and the Department of Homeland Security, which has called the device a “puke ray,” the LED Incapacitator also causes dizziness, vertigo and nausea.

Mazzara insists those reports are purely anecdotal and that there is no evidence of any nonlethal weapon causing any such sickness, as it would not be an effective technique, given that some people are more prone to nausea than others.

Even so, Danger Room, Wired Magazine’s blog on defense technologies, reported in December that the INLDT was developing a device that combined “aversive noises with light to produce some special debilitating effects.” Reporter Sharon Weinberger called it “another potential ‘puke ray.’” But if you ask the INLDT, it is more like a “PA system on steroids.”

Named the Distributed Sound and Light Array Debilitator, its aim is “to be used on land at security checkpoints to stop vehicles and onboard ships or helicopters to hail approaching small watercrafts,” Mazzara said. Beaver Stadium was one of the test sites this summer, and Mazzara has bragged the device could be heard more than a mile away.

Whether or not it also produces that undesirable effect of nausea—something Weinberger concedes is based on purely anecdotal evidence—the long-term effects of nonlethal weapons need more consideration. For instance, when it comes to acoustic devices like the DSLAD, very little is known, and may not be known until the damage is done.

In reporting on another acoustic device being developed by INLDT—nicknamed “sonic blaster” by Danger Room—Weinberger noted, “There isn’t really any reliable data on the effects on humans as you move up the decibel range.” But due to current safety standards, human testing can only be conducted up to a certain decibel level, a level the INLDT has called “far too conservative.”

Although Mazzara could not comment on “specific protocols under consideration” by Penn State’s institutional review board, the committee that governs all research involving humans, the INLDT has reportedly sought approval to conduct testing at 130 decibels to see if sound can force “behavior modification.” But according to Weinberger, “The problem with making this into a weapon is that it is hard, perhaps even impossible, to develop a device that can really deter an aggressor without damaging their hearing.”

Winning friends and influencing people

This issue highlights the dilemma facing the developing field of nonlethal weapons. If the objective is to usher in an age where the children of the world perceive U.S. soldiers as peacekeepers—a declared objective in the INLDT’s work—then, clearly, nonlethal weapons need to be far less horrifying and injurious than current models.

Even if that were somehow achievable—which goes against the very nature of weaponry—the idea of U.S. forces being received with open arms based solely on the use of less-deadly weapons completely belies the intentions of U.S. foreign policy, which former U.S. Attorney General Ramsey Clark once called “the greatest crime since World War II.”

It’s not hard to see why. U.S. military force has been used 45 times in nearly 30 countries since 1947, involving the overthrow of democratically elected leaders, the installation of brutal dictators and the deaths of millions of civilians. Not only do those involved in the development of nonlethal weapons see no stop to interventions of this sort, they expect their products to be of great import.

On its Web site, the INLDT says, “The roles of the U.S. military and the nature of the threat to our forces have significantly changed over the past two decades as illustrated by U.S. interventions in Panama, Somalia, Haiti and Bosnia. These engagements, unlike those anticipated during the Cold War era, were against small units that were armed with inferior, yet effective, weapons and that often used the civilian populace as a shield.”

While that may be an accurate assessment, it says nothing about what those interventions were about and why insurgencies sprung up. One big reason is that the United States had been a longtime supporter of hated dictatorships in Panama, Somalia and Haiti. So it seems doubtful that nonlethal weapons can overcome years of aggressive foreign policy—a rather foreboding prospect given the historically lethal role the United States has played in the Middle East, for example.

If nonlethal weapons fail in their effort to foster fewer enemies, then they will surely fail in their other objective, which is to generate positive PR on the home front. As the percentage of civilian deaths increases with each new war—up to 90 percent of total deaths in Iraq and Afghanistan, as opposed to 70 percent in Vietnam and 50 percent in World War II—so does the level of dissent by the American people.

Given that scenario, it seems more likely that nonlethal weapons will be used on protest lines than on the front lines abroad. In preparing for this year’s Republican National Convention, the St. Paul Police Department ordered enough Tasers to equip every officer—a precaution that’s clearly aimed at preventing a repeat of the 2004 RNC in New York City, where more than 1,800 individuals were arrested.

There’s also the microwave-like “pain ray,” called the Active Denial System, which causes a serious burning sensation on the skin. (Our INLDT didn’t get to test this one.) It’s very close to being deployed in Iraq, but not before—as Pentagon officials have suggested—it is first used on “American citizens in crowd-control situations.” 60 Minutes ran a segment in March on this device in which military personnel posing as peaceful protestors—carrying signs that read “Love for All” and “World Peace”—got zapped by the pain ray and quickly retreated.

With more supposedly nonlethal weapons entering the market—essentially offering police the excuse of an easy and less messy way to solve a problem—displays of First Amendment rights will likely become even more infrequent. This serves to show that the military’s idea of altruism is just another form of repression.

Demilitarizing college campuses

It’s important that Americans realize that the biggest deterrent to war and violence is not the creation of less lethal fighting instruments, but rather citizens promoting a worldview that questions the motives of those who say war and violence are needed in the first place. And what better place is there to develop and promote such a worldview than in the classrooms and on campuses in our own country?

Sen. J. William Fulbright, namesake of the Fulbright Scholar Program, warned that “in lending itself too much to the purposes of government, a university fails its higher purposes.”

Those tied to what Fulbright called the “military-industrial-academic complex” may argue that schools would suffer and whole fields of study would be crippled without funding from the Defense Department. But according to Nick Turse, a defense expert and author of the book The Complex: How the Military Invades Our Everyday Lives, “No one ever explains why all this federal money (to universities) needs to flow through the organization charged with war-making.”

“There isn’t any compelling reason why the Pentagon has to be the top federal agency to fund fields of high-tech research or be the major federal funder of electrical engineering,” he said. “I imagine that if, say, the Environmental Protection Agency was the major funder, research thrusts would be radically different and would not, likely, end up furthering lethal technologies or war-making capabilities.”

That may seem like a tough proposition for a school that’s staked its reputation on a strong defense—both in football and academics—but it’s something for students to think about while they pay their taxes and tuition and pay off their loans before entering a faltering job market. Perhaps the next time they’re crammed into the stands at Beaver Stadium and asked to applaud the choice to join the military, they’ll realize that they’ve already been enlisted.

Bryan Farrell graduated from Penn State in 2004 and has since become a New York–based journalist and activist. His work has appeared in many publications, including The Nation and In These Times. He can be contacted at http://bryanfarrell.com.

Comments

Years of Crises: The 1960s

I would add that work at Penn State exposing military research had begun as early as 1967. Penn State SDS took up the work that Columbia SDS had done on the Institute for Defense Analyses that led to the occupation of Low Library in 1968. Education campaigns at Penn State in the dorms, publication of the student research in an SDS newsletter, SOUTHPAW, and petitioning was incorporated in this campaign. The Ordinance Research Lab was the name of the facility that you call the Applied Research Lab in your article. The Garfield Thomas Water Tunnel was a torpedo testing facility on campus that was adopted as the name of the local underground newspaper.

Martin Zehr

Penn State

Class of '71