MINOR: Our movies need new stories

In February, I went to the State Theatre for a screening of this year’s Oscar nominations for best live action short film. This is what I saw: White people in Denmark, England, and France dealing with a range of experiences (terminal illness, domestic violence, questions about self and God), and black people somewhere in Africa chanting “blood, blood, blood,” armed to the teeth, psychologically torturing and murdering white European doctors, and raping a white woman.

I want to think that this was an isolated incident, an accidental conglomeration of images that reinforce the same old dehumanizing story: White people are emotionally complex, they live nuanced lives, they can be doctors or poor or gay or straight, they have names, while black people are one-dimensional, nameless, either savage or repentant, but never fully human—that is, complicated.

But, if this is an isolated incident, where are the images, in these and all the other Oscar-nominated films this year and every other year, of black people falling in love, black people going to work, black people starting businesses or mending relationships or dealing with illness, or wondering about the stars?

Instead, we have Spanish director Esteban Crespo’s short film Aquel No Era Yo (That Wasn’t Me), a befuddling tangle of apparently good intentions and poor choices. Aiming to educate audiences about the lives of African child soldiers, the film re-inscribes many of the most dehumanizing stories Westerners have told about Africans. Aiming to uncover injustices done to children, it perpetuates the injustices of misogyny, racism, and colonialism. Perhaps most disturbingly, Aquel No Era Yo aims to “raise awareness,” but feels woefully unaware, itself.

Filmed in a style somewhere between faux-documentary and box office action hit, Crespo’s film tells the story of an African child soldier, Kaney. (I wasn’t able to learn, from the film or from its website, exactly where in Africa the film is intended to take place.) Most of the film’s 24 minutes focus on graphic, explosive violence—in the opening scenes, we watch Kaney and other children ordered to shoot the kidnapped, weeping European doctors kneeling in front of them. We watch one of the doctors, Paula, who has been kept alive for this purpose, raped by one of the soldiers. A few plot twists and explosions later (critics have praised the film’s “big budget” look), and Paula escapes, dragging Kaney with her. Through flash forwards, we briefly see an older Kaney speaking about his experiences to an auditorium full of white Europeans. The end.

I’ve thought a lot, since seeing this film, about the kinds of questions and intentions that might go into the making of such a story. As an artist, I often struggle against the supposed dichotomy between politics and aesthetics, and I’m interested in the ways that skilled creative people bridge and erase that dichotomy. Ultimately, I’m hardly shocked that an Oscar-nominated film failed to do something politically sensitive or to be aesthetically nuanced, but what disturbs me about Crespo’s film is its failure to understand the connection between political and aesthetic aims. Here are some of the questions Aquel No Era Yo raised for me, and that it seems the people involved in making and nominating the film forgot to ask:

When was the last time white European doctors were kidnapped, tortured, and raped by African child soldiers and their adult leaders? If the film aims to raise awareness about real-world issues, why introduce this fantastical, pronouncedly un-real-world plot element that does more to re-inscribe narratives about black violence against white people than to humanize Africans?

Is showing a bunch of nameless, vicious people in an anonymous African country the best way to encourage empathy for child soldiers?

What are the intentions and effects of writing, staging, and filming a graphic scene of sexual violence? When the woman who is the victim of such violence is not the central character, when the story focuses, in fact, on the victimization of the children brutalized by the men who rape her, what value does such a scene contribute? From where does the motivation to write and film such a scene come?

In staging scenes of torture and sexual violence, I’m not sure the filmmakers thought about exactly what they were inspiring, what fantasies and narratives they were perpetuating, what pleasures they were invoking. I’m not sure anyone asked those most basic creative questions: “Is this our story to tell?” and, “How should we tell it?” And so I left the theatre wondering, and I’m still wondering, exactly of what is our awareness being raised?

This last question leads me to a final one, a question about perspective: If the filmmakers were deeply interested in documenting the real, lasting effects of trauma, why did no one ask how the film itself would affect survivors of trauma? Does a movie that attempts to deal with trauma need to re-inscribe trauma? Why did no one wonder, finally, who this film was for?

I don’t think Aquel No Era Yo is, at its heart, concerned with how people live through trauma. There is a thinly veiled layer of pleasure—not empathy—underlying the filming of its most horrific scenes. The film does not seek to unravel any of the most basic oppressive assumptions it invokes, assumptions about black men and white women and sexual violence; assumptions about Africa and brutality; assumptions about the West as a redemptive force for a continent of savage people; assumptions about who is fully, complexly human and who is not. The film is for, in the end, those whose sense of self relies on these assumptions. Although it masquerades as a story about marginalized people, it is by and for white, male, Western eyes.

Art, if it is art, enlarges our sense of what it means to live and feel in the world. Living through trauma is complex. In failing to look at its subject complexly, in failing to enlarge our sense of what it means to be in the world, Aquel No Era Yo fails as a document of trauma, and it also fails as art.

I think it’s time we start asking for, expecting, and telling other stories. ■

Whitey Blue weighs in on State Patty’s Day

I was talking the other day to Whitey Blue, longtime Centre Region resident and hardnose.

Whitey, any comments about the relatively quiet State Patty’s Day in State College this March?

“It was too darned peaceful! We need some spirit and spunk, some good old-fashioned, rip-snortin’ Hell-raisin’!”

That would harm too many innocent people who just happen to be in downtown State College that day!

“Let ‘em stay home and sit by their firesides sipping tea, and let the student celebrants have their fun!”

— David M. Silverman

(Who had his rip-snortin’ drinking days overseas in the U.S. Army in WWII at times when he wasn’t in combat.)

Letters to the Editor

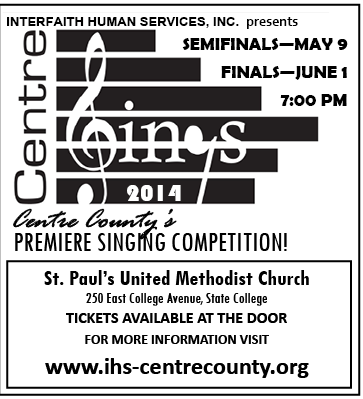

Music scene? What music scene?

I read Renae Gornick’s “Breaking Into the Music Scene in State College” (March 2014 issue) with interest. However, Gornick’s article only further confirmed for me that there IS no “music scene” in State College.

The fact is (as the article makes clear), State College has a limited set of venues for live music that offer coveted weekly performance slots for musically conservative bands playing a narrow range of familiar and predictable covers of contemporary rock and pop songs.

As Michael Caruso, manager at the Darkhorse, states, “it doesn’t necessarily matter how good (the band is) as long as they can bring in a crowd.”

And as Pat Usher, singer in a local band relates, “I write my own music and was looking for a place to play…but I kind of realized that no one in this town wants to hear original music.”

It’s a mystery (and a shame) that the local music mainstream in State College is so sterile and uninteresting, while other comparable university towns are able to support thriving and aesthetically challenging musical and artistic communities (for example, Chapel Hill, NC, Austin, TX, and Ithaca, NY to name just a few).

Gornick doesn’t take this question on. Nor does she expend any effort to identify local musicians, bands and venues within Centre County and the surrounding areas that intentionally take risks all the time in pursuit of new and visionary musical and artistic directions.

Kai Schafft

Millheim, PA

Kai,

It is indeed a mystery and a shame that State College lacks the thriving original music scene found in other college towns. Ms. Gornick’s article was written in part to draw attention to this.

We’re always happy to write about about new artists and venues in the greater Centre County area as we discover them.

Thanks for reading, and for taking the time to write.

Sean Flynn

Managing Editor

Kudos for an issue well done

The March issue looks great. Please pass along my compliments to Sean and the others who put it together.

Several of the stories are harder hitting, better researched and better written and edited, and all the content is laid out much better in terms of nearby jump pages.

Well done.

Katherine Watt

Editor and Publisher

Steady State College

State College, Pa.