Maryland Army National Guard Soldiers and local law enforcement watch protesters gathered in front of City Hall, Baltimore, April 30, 2015

Photo by U.S. Army National Guard Sgt Margaret Taylor WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

By: SHARON BARNEY

[email protected]

David Flores saw community members line the streets of the Western District of Baltimore 24 hours after Freddie Gray died. “There was a lot of deep tension, anger, pain, and raw emotional energy that was coming out,” Flores said. “People were calling out black police officers for protecting their own instead of protecting the community. Some of the police officers started crying. It was stunning to see.”

The story of Freddie Gray’s arrest and death has had a widespread impact. Gray, a 25-year-old black man living in Baltimore’s Western District, was arrested on April 12, 2015. Police officers claimed that he was in possession of an illegal switchblade, although a later investigation showed that his pocket knife was legal. Between 8:39 a.m. and 9:24 a.m. that morning, the police van carrying Gray made four stops, not one of them to a medical center. Yet Gray suffered a critical neck injury. News of Gray’s mistreatment and subsequent coma spread through the community, and hundreds of Baltimoreans protested outside of the Western District police station. Tragically, Gray died on April 19.

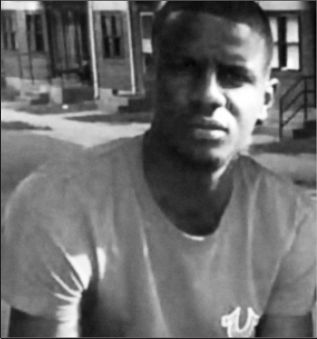

A photo of Freddie Gray

Photo by Source (WP:NFCC#4)// WIKIPEDIA.ORG

Flores, a lifelong resident of Baltimore and current law student at the University of Maryland School of Law, volunteered to be a legal observer during the protests, someone who ensures that police and government actors are held accountable if they violate protesters’ constitutional rights. “We would make sure that those arrested would be connected with legal support if they needed it,” Flores said.

There were plenty who needed legal support. At least 486 protesters were arrested, with charges ranging from disorderly conduct to burglary and assault. Some were kept in jail for over 48 hours without being officially charged with a crime, while others were kept even longer. The mandatory curfew of 10 p.m. in certain parts of the city added to the number of arrestees. Enforcement of the curfew highlighted the continuing issues and tensions related to race and income level. Flores noted that there was hardly any police activity to enforce the curfew in white, affluent neighborhoods, while the police officers were concentrated in poor, black neighborhoods. White protestors out after 10 p.m. were given numerous notices and chances to leave the area past the curfew, and many were not arrested. Black protestors were grabbed, pepper- sprayed, and shackled if they were seen out past 10p.m.

“During the first few days, the protests were very visceral,” Flores says. There was little chanting and few signs. It was pure emotion tied to decades of living in a complicated city with a long history of segregation. Baltimore is described as being two cities - an affluent, racially and ethnically diverse center, surrounded by the Eastern and Western Districts, which are low-income and predominantly black.

Surprisingly, on May 1, Marilyn Mosby, the state’s attorney in Baltimore, announced that criminal charges would be filed against the six police officers responsible for Gray’s arrest. The charges ranged from second- degree murder, the most serious charge, against Officer Caesar Goodson, Jr., to assault, manslaughter, false imprisonment, and misconduct in office. Flores was in the Penn North district when the charges were announced. The emotion among the protestors was less pain, more exuberance. Disturbingly, in contrast to the crowd’s enthusiasm, law enforcement presence increased and became more militarized. "There were tanks, high assault rifles, it looked like a war zone." Flores said.

Flores was in the Penn North district when the charges were announced. The emotion among the protestors was less pain, more exuberance. Disturbingly, in contrast to the crowd’s enthusiasm, law enforcement presence increased and became more militarized. “There were tanks, high assault rifles…it looked like a war zone,”

Things have quieted down in Baltimore. A “new normal” has spread across the city. There is still ongoing tension. Some believe that Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake went too far in the law enforcement action and policies that were implemented. Others believe she did not go far enough to prevent looting and property damage, especially in the outskirts of the city. But one thing is certain: the protests have sparked a continuing dialogue in the city and nationally, about issues relating to race, police militarization, income inequality, and governmental accountability.

More protests, anger, and attention will come to Baltimore once the trials for the six police officers begin, but Flores remains optimistic. “We did not bring a revolution to a city (through the protests),” Flores says, “but I hope there is a revolution in the way people from the community view the inequality in services, opportunities and policing between the two Baltimores. We need realistic expectations and a meaningful response.”

Sharon Barney practices immigration law, family law, employment law, and victim rights law in the Centre County region.