By Charles Dumas

We were invited to a class taught by Courtney Morris, Asst. Prof. Anne Marie Mingo, Prof. Paul Taylor head of the African-American Studies Department. It was a workshop on the events around Ferguson. Several police chiefs and Penn State officials also attended. The students had examined various aspects of the events in Ferguson, MO, focusing on: the police, the media, state officials,demonstrators, etc.

Much attention has been paid to white police officers, killing unarmed African-American men. Relatively little attention has been focused on the community reactions to the incidents after they have occurred. Thousands of people in Ferguson and across the nation participated in demonstrations,die-ins, and other expressions of community action. Almost all have been peaceful, the people exercising their Constitutional rights to assemble to petition the government about their grievances. I believe there is no activity that better exemplifies the American character and spirit. It is part of our DNA. But, how do the demonstrations in Ferguson and elsewhere measure against similar instances of collective community action?

From the very beginning of our Democracy, the people have assembled to make known their positions on: taxation without representation, slavery, women’s suffrage, prohibition, 40 hour weeks and decent working conditions, pro and antiwar, civil rights, anti-abortion,prochoice, gay rights, and global warming to name a few. Gatherings of the people related to race have been particularly prominent.

In August of 1965, I was a civil rights organizer in California. We heard that folks were“rioting” down in Watts. Our first question was; Where is Watts? Watts was a Black ghetto in the South Central area of Los Angeles. It was a depressingly poor and deprived area. During an ordinary DUI arrest several police officers had allegedly roughed up a 21 year old Black man named Marquette Frye. During the arrest Frye’s brother and mother arrived from their house nearby. A crowd gathered. There was some pushing and shoving. Over a hundred hostile citizens surrounded the police car. Somewhere a fire started, bottles were thrown. Years of pent-up frustration began to surface. The uprising was on.

The following day helicopter shots showed fires burning in the area, but there was limited coverage from inside Watts. Several of us decided that we should go down to LA to see what was happening for ourselves. It was a war zone. The police had cordoned off and stayed out of the affected areas in an attempt to contain the violence. Though hundreds of fires were burning, the fire department was not going into the area to put them out. In the beginning when a few had tried, they were attacked by folks shouting, “Burn, Baby, Burn!” Stores were looted. Most of these stores had absentee owners. The ones owned or leased by people from the neighborhood were generally passed over.

Interestingly enough, though evidence of arson and burglary were everywhere, there was very little “one- on- one” crime. There was a feeling of solidarity among the mostly young people on the street. Though there were no police, people did not act afraid. They were jovial. Some began calling it, “liberated territory.” Strangers greeted each other with, “Right on brother. Freedom, sister! “

The Watts Uprising lasted six days. It is estimated that 35,000 people participated and another 70, 000 were sympathetic. 3, 438 people were arrested,1,132 were injured and at least 34 rioters were killed. It was just two years after The March on Washington. It signaled a dramatic shift in Black people’s public response to racial discrimination. It was similar to the response of the people in Ferguson except Watts was spontaneous and unorganized. Also the protests in Ferguson and elsewhere rarely became violent except when the police exercised what might be considered excessive force.

In April of 1968 I was in Washington D.C. organizing for the Poor People’s Campaign. It was announced that Martin Luther King had been assassinated in Memphis. People were angry and hurt. The City erupted. Unlike their response in Watts, the police did not withdraw. There was more violence. In the end, 12 people were killed, over a thousand were injured, and over 6,000 were arrested. 110 other cities also had major riots. Chicago, Detroit and Baltimore were the worst.

Like Ferguson, the riots around the King assassination were triggered by a single incident, and tapped into a wellspring of pent-up frustration and outrage. It was exacerbated by the fact that Dr. King was known to be a man of nonviolence and peace. His killing was clearly considered by most Americans as unjust. The killing of an unarmed man in Ferguson was also considered by many, both Black and White, as unjust. The failure of the grand jury to indict the police officer involved was seen by many as piling injustice on top of injustice.

In 1992 I was finishing up graduate studies at the American Film Institute in Los Angeles when the Rodney King riots broke out. Ultimately over 53 people died, 2,000 were injured. 3,500 fires were set which destroyed over a thousand buildings. King had been arrested on a DUI in March of 1991. During the arrest he was kicked and severely beaten by officers as he crawled on the ground. Black folks knew that this kind of behavior was common for the LA police, though authorities denied it. This time the incident had been captured on video. The officers involved were not charged at first. After the video was released, the LA District Attorney charged four of them with excessive use of force. It was determined that the officers could not get a fair trial in LA, so the venue was changed to a nearby predominantly white community. A predominantly white jury acquitted the officers of any wrongdoing. “They were just doing their job”. Black people who had been watching the trial on TV were outraged. Years later the Ferguson grand jury said the same thing. Despite obvious injustice of the outcomes- a brutalized defenseless man, and a dead unarmed one- the police were just doing their job, protecting life and property.

Finally a similar but not identical situation that did not involve race. On November 9, 2011 the Penn State Board of Trustees fired Coach Joe Paterno. Almost immediately thousands of angry students poured out to College and Beaver Avenues, screaming and shouting. Like the people in Ferguson they felt hurt and betrayed. They tore down light poles and damaged other property. In their frustration over the treatment of their beloved coach, the students vented against what they perceived was the available “enemy”, the media. They attacked a TV van and shouted obscenities at reporters. My wife and I were out on College Avenue. We often had to intercede between angry students and frightened reporters. The police showed great restraint. There were a few injuries, some property damage. Later there were some indictments but no one was killed or grievously injured. No houses burned.

I am not arguing that the Ferguson demonstrations, Watts Uprising, King assassination disturbances, Rodney King riots and the riots after Paterno was fired are all the same. Though they share the fact that all of them involved 1) people reacting to a perceived wrong by public authority, 2) a police reaction with an attempt to restore and protect order, 3) confrontation between police and protesting citizens with the use of force, which is sometimes deadly. They are also examples of people seeking ways to make their feelings known. It is not pretty but it is democracy in action.

What is the role of the police in these circumstances? Certainly, to protect life and limb and prevent injury, under most circumstances to protect property. They are permitted, indeed required, to use necessary force to accomplish the tasks. What is necessary force? Certainly we would all agree that force, even deadly force, should be used to save lives, stop arson,prevent great physical harm to others. But, should the use of deadly force be allowed to prevent someone from shoplifting, fleeing an arrest warrant, singing too loud or shouting obscenities at officers? When necessary,shouldn’t police action also be used to protect citizens in their free exercise of their Constitutional rights to assemble and petition the government about their grievances?

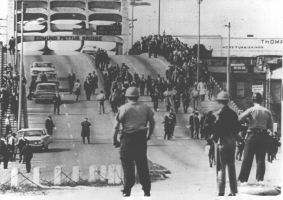

Edmund Pettus Bridge on Bloody Sunday

Fifty years ago a group of American citizens in Selma set out to march to their State capital to demand their righ to vote. As they crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge the Alabama state police, acting in accordance with the law and to protect the public order, attacked them and beat them mercilessly. Several people were even killed later by persons yet unidentified or prosecuted. In the hindsight of history we know that those officers were morally wrong and committed an act of human indecency. But, they were following the law and maintaining the order of the time. But,the presumed “illegal” action of those marchers helped changed the immoral law of racial discrimination.

A couple of months ago, 50,000people marched across that same bridge. Led by two United States presidents,one black and one white, they sang and celebrated. They snapped pictures with their children and old civil rights veterans who had been at the bridge before. The police walked in front and behind the crowd to make sure that their fellow citizens would be safe exercising their Constitutional right to assemble and commemorate a sacred day of remembrance and transformation. I believe that is also a proper role of the police in our society.